Main Theme

Sub-theme: plastic pollution; landfills; waste management; artificial intelligence; open data.

Abstract

Can the power of artificial intelligence be used in environmental protection?

Plastic pollution is one of the most critical threats to the health of ecosystems, animal life, and human life. All over the world, initiatives aimed at recovering plastics, particularly those found in the oceans, are multiplying in a wide variety of ways. Most of the plastic we find in the ocean comes from land: it flows downstream through rivers to the sea and can soon be picked up by rotating ocean currents and transported anywhere in the world. However, plastic waste deposits on earth are not only those known as landfills and recycling centres: there are thousands of illegal deposits everywhere in the world, which, precisely because they are uncontrolled, contribute to making plastic pollution even more dangerous and indiscriminate.

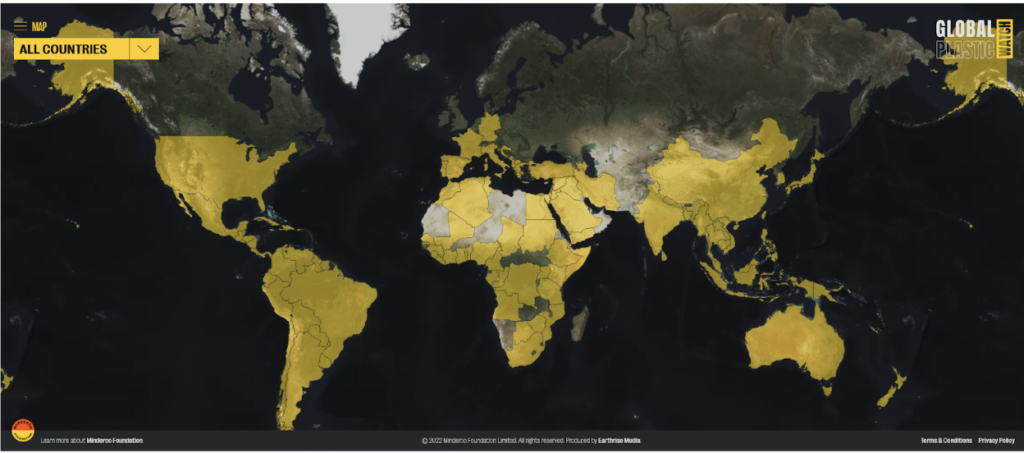

For this reason, Minderoo Foundation and Earthrise Media have launched the Global Plastic Watch platform. The project aims to monitor unreported deposits of plastic waste worldwide, thanks to the use of public data provided by European Space Agency satellites and the development of an artificial intelligence system. It is currently the largest open-source dataset of plastic waste in dozens of countries. The Global Plastic Watch serves as a tool that governments, funding agencies, intergovernmental organisations, NGOs, scientific researchers and the general public can use to make evidence-based decisions on managing and mitigating the world’s plastic pollution problem.

Artificial intelligence is now widely funded worldwide, and its applications are multiplying. One of the fields that could be most promising is environmental protection, as seen in previous projects mapping individual tree canopies or locating and monitoring otherwise hard-to-regulate industries (like brick kilns or potentially polluting animal farms).

Sustainable Development Goals Chart

Main Highlights

Problem: plastic pollution threatens ecosystems, animal and human health.

Context: most of the plastic we find in the ocean comes from land, and there are thousands of unmonitored illegal dumps.

Solution: using open source satellite images and AI trained softwares, the Global Plastic Watch maps legal and illegal plastic dumps in the world, and publishes the results for free.

Impact Statement: over 4,000 sites found, 1,056 (26%) are within 250m of a waterway, a further 497 sites (12%) are within 100m of a waterway.

Systems Perspective: the use of open data and AI in ecological monitoring and pollution prevention can be a turning point in how we tackle those issues.

Case Overview

Picture from the GPW website: https://globalplasticwatch.org/

Plastic pollution is a recurring theme on the agenda of more and more non-governmental organisations and national and international institutions. It is no news that it is one of the most critical threats to the health of ecosystems, animal life, and human life. All over the world, initiatives aimed at recovering plastics, particularly those found in the oceans, are multiplying in a wide variety of ways – we have often spoken about them, including in the cases presented by various 4Revs researchers. Plastic objects, dispersed in the environment indiscriminately, end up in the seas in one way or another, bringing with them a series of consequences: the semi-degraded waste can suffocate, strangle, injure and be ingested by animals, threatening their survival, and the floating rubbish can carry invasive species that risk destroying fragile ecosystems. As far as human life is concerned, plastic degradation to the micro-plastic stage (small fragments) means that it has entered the food chain and can now be found everywhere: in drinking water, in salt, and in the soil where the crops we eat grow. Plastics are carcinogenic and affect the endocrine system, causing developmental, neurological, reproductive and immune disorders. Not only that, toxic pollutants often accumulate on the surface of the plastic in the oceans that we eat when we consume fish or shellfish.

Picture from Pexels distributed in CC. Photo by Tom Fisk taken in Indonesia.

As mentioned, most of the plastic we find in the ocean comes from land: it flows downstream through rivers to the sea. At first, it may stay in coastal waters, but it can soon be picked up by rotating ocean currents, called gyres, and transported anywhere in the world. However, plastic waste deposits on earth are not only those known as landfills and recycling centres: there are thousands of illegal deposits everywhere in the world, which, precisely because they are uncontrolled, contribute to making plastic pollution even more dangerous and indiscriminate. For this reason, Minderoo Foundation and Earthrise Media have launched the Global Plastic Watch project.

The Minderoo Foundation is an Australian philanthropic organisation founded in 2013 that incubates ideas and accelerates impact with AUD $1.5 billion committed to a range of global initiatives and causes. These causes range from eliminating childhood cancer to improving early childhood education, ending modern slavery and driving accountability in and responsibility for global overfishing, plastic pollution, global warming and the tech ecosystem. Together with the University of Queensland, they created the Minderoo Centre – Plastics and Human Health, dedicated to understanding more about human exposure to plastic particles and chemicals, developing methods to sample and measure plastic chemicals and particles in humans accurately, and in particular, human brains.

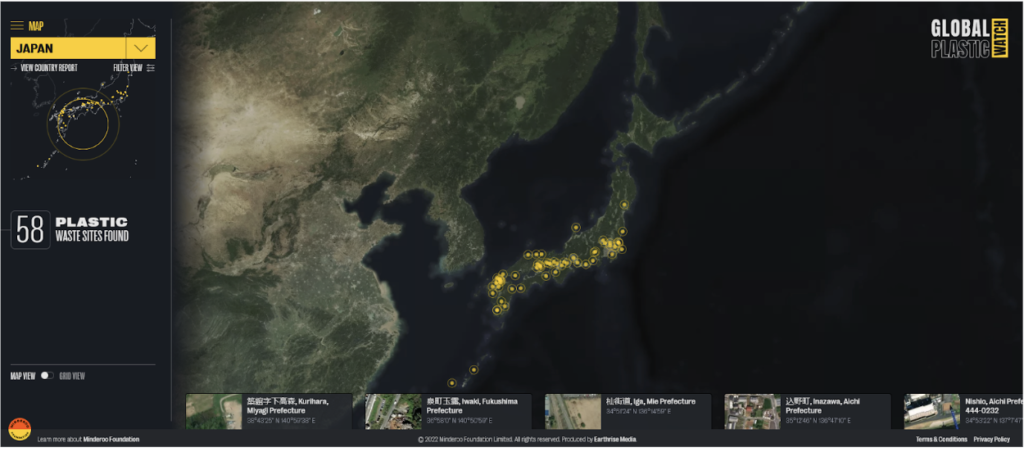

Furthermore, that is not all: to minimise plastic pollution of the oceans, the foundation has set up the Global Plastic Watch project, which aims to monitor unreported deposits of plastic waste around the world, thanks to the use of public data provided by European Space Agency satellites and the development of an artificial intelligence system. GPW is a digital platform that maps the world’s plastic pollution in near real-time, detecting plastic waste sites on land and monitoring them over time. It is currently the largest open-source dataset of plastic waste in dozens of countries. The data gathered provides a historical first and authoritative insight into one of the world’s most intractable environmental challenges and, thanks to the first-of-its-kind machine-learned model, can determine the size and scale of land-based plastic waste sites. Using these combined technologies is crucial since most of the data about plastic waste so far come from models and estimates: with the GPW platform, the understanding of the phenomenon is informed by accurate data that can be used to guide solutions.

Currently, Global Plastic Watch can:

- Identify waste sites to enable site clean-ups and better enforcement of laws against dumping.

- Provide risk indicators for existing plastic waste sites, such as proximity to water or communities.

- Highlight priority areas for investment: namely, investment in waste and recycling infrastructure.

- Demonstrate visible progress towards waste management targets.

The Global Plastic Watch serves as a tool that governments, funding agencies, intergovernmental organisations, NGOs, scientific researchers and the general public can use to make evidence-based decisions on managing and mitigating the world’s plastic pollution problem. In fact, the government of Indonesia is working with Minderoo Foundation to increase its recycling capacity to double recycling rates by developing capacity for an additional one million tonnes per year by 2025.

How does it work?

The project website explains, “The methodology behind GPW is explained in detail in a virtual data story here. In training the models, we began with only 10 known waste sites on the island of Bali. We iterated on early model outputs and incorporated new data until the models achieved sufficient skill to operate over the whole of South-East Asia, Australia, and countries in South Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, Central and South America. Deployed on the Descartes Labs geospatial analytics platform, the system has returned three-times more validated waste sites compared to OpenStreetMap (the previous best-available global dataset). The approach allows for a repeatable, scalable, cost-effective, and operational monitoring capability for plastic waste on land.”

The current version of the GPW collects the following data points:

- Location of formal and informal land-based waste aggregations containing plastic waste, including micro dumpsites (as small as 25 m2)

- Validation of land-based waste aggregations through Google Street View or high-resolution satellite imagery

- Temporal trends in the extent of the surface area of land-based waste aggregations, month-to-month, as far back as early 2017

- The proximity of land-based waste aggregations to rivers and water bodies, including 12 metadata parameters that are relevant in terms of leakage, including upstream drainage area, slope, and soil composition.

The platform is public, and anyone can inform or stay up-to-date on illegal plastic waste dumps that the system detects and registers online. Below are some screenshots taken from the Global Plastic Watch website showing the information that can be obtained: where it is located, Street View from Google Maps, changes occurred in time, the closeness to water and more site attributes.

Sources:

https://globalplasticwatch.org/

Satellite Monitoring of Terrestrial Plastic Waste https://arxiv.org/abs/2204.01485

Unesco’s Ocean Literacy: https://oceanliteracy.unesco.org/plastic-pollution-ocean/

https://globalplasticwatch.org/

Satellite Monitoring of Terrestrial Plastic Waste https://arxiv.org/abs/2204.01485

Unesco’s Ocean Literacy: https://oceanliteracy.unesco.org/plastic-pollution-ocean/

Impact Statement

Global Plastic Watch key figures:

- Over 25 per cent of sites are within 250m of a waterway. Of the 3,999 sites found, 1,056 (26%) are within 250m of a waterway. A further 497 sites (12%) are within 100m of a waterway.

- Global Plastic Watch can detect plastic waste sites as small as 5 by 5 metres.

- On average, 5,576 people live within 1km of a site, and 129,886 people live within 5km.

- The number of large-scale sites is more significant than imagined. Many large-scale waste sites Global Plastic Watch has mapped were previously undocumented, and the number of sites is much higher than expected.

Plastic Pollution Key Facts:

- Plastic waste makes up 80% of all marine pollution, and around 8 to 10 million metric tons of plastic end up in the ocean each year.

- Research states that, by 2050, plastic will likely outweigh all fish in the sea.

- We have produced more plastic products in the last ten years than in the previous century.

- The EPA (UN Environmental Protection Agency) has stated that 100% of all plastics humans have ever created are still in existence.

- Plastic generally takes between 500-1000 years to degrade. Even then, it becomes microplastics without fully degrading.

- Currently, about 50-75 trillion pieces of plastic and microplastics are in the ocean.

- This plastic either breaks down into microplastic particles or floats around and ends up forming garbage patches.

Sources:

Systems Perspective

The issue of plastic pollution has further consequences in addition to those already listed. Firstly, there is the climate impact and air pollution produced by the transformation of oil into plastics and the treatment of plastic waste when it is incinerated – i.e. dispersing carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere. Nevertheless, the economic impact is also not insignificant: according to some estimates, the annual cost of plastic in the oceans is between 6 and 9 billion dollars, considering the effects on tourism, fishing and aquaculture, and public interventions to remove waste from the sea.

The most effective strategies, therefore, involve working at the source of the problem, minimising the production of new plastic and avoiding single-use plastic at all, and increasing methods to recycle existing plastic (complex due to the different types of plastic often combined in the same objects and the availability of appropriate machinery and facilities) and investing in keeping as much material as possible within waste management. In fact, efficient waste management is crucial, and, unfortunately, not all countries in the world have adequate policies and/or sufficient funds to keep the second raw material in use.

Not only that: even countries considered to be the most efficient in recycling, such as Japan, show a more complex picture when looked at closely. According to the Tokyo-based Plastic Waste Management Institute, in 2020, only 21% of plastic waste underwent material recycling, which reuses plastic; 3% underwent chemical recycling, which breaks down plastic polymers into building blocks for secondary materials. 8% was incinerated, while 6% went to landfills. 63% of plastic waste was processed as “thermal recycling,” which involves using plastic as an ingredient for solid fuel and burning it for energy. Furthermore, in 2020, Japan exported 820,000 tonnes of plastic waste to South East Asian countries such as Malaysia, Thailand, and Taiwan – roughly 46% of the total.

A further problem is the illegal dumps scattered all over the planet. Through the work of Global Plastic Watch, we have seen that the use of artificial intelligence and public and open data provided by European satellites can help combat this phenomenon. The project, however, is still at a relatively early stage, given the exorbitant amount of additional small or medium-sized waste dumps scattered around the world that the system has not yet been able to track. Artificial intelligence, at this point, is widely funded worldwide, and its applications are multiplying. One of the fields that could be most promising is environmental protection. The idea is not new: already in 2020, a study was published in Nature that used satellite images and AI to map over 1.8 billion individual tree canopies across millions of kilometres of the Sahel and Sahara regions of West Africa. In this case, the researchers employed neural networks which are able to recognise objects, like trees, based on their shapes and colours. To train it, the AI system was shown satellite images where trees had been manually traced. In another case, artificial intelligence combined with satellite imagery provided a low-cost, scalable method for locating and monitoring otherwise hard-to-regulate industries (like brick kilns or potentially polluting animal farms). The Global Plastic Watch project, however, is the first application towards plastic deposits and could potentially transform how we tackle plastic pollution.

Sources:

https://oceanliteracy.unesco.org/plastic-pollution-ocean/

https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20220823-quitting-single-use-plastic-in-japan

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1470160X22004575?via%3Dihub

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-020-2824-5

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2018863118

https://news.stanford.edu/2019/04/08/machine-learning-can-help-environmental-regulators/

Links and Contact Information

Links

Company website: https://globalplasticwatch.org/

Co-founders: https://www.minderoo.org/about/co-founders/

Contact: gpw@minderoo.org

Social media accounts

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/company/no-plastic-waste/ / https://www.linkedin.com/company/minderoo/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/no_plasticwaste/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/NoPlasticWaste2019

Twitter: https://twitter.com/No_PlasticWaste

Article by: 4Revs Researcher Ilaria Nicoletta Brambilla | April 2023