Abstract

There are growing expectations that sustainable investing – investing that takes environmental, social, and governance (ESG) information into account – will contribute to the achievement of societal goals. In order for the 2030 EU climate target to be met, €350 billion annual increase in investments in sustainable businesses is required. However, defining what makes an investment or fund sustainable is a difficult task without clear guidelines or standardized reporting, and greenwashing is of particular concern.

In December 2019, the European Union (EU) made a giant step towards the regulation of sustainability-related disclosures with the advent of the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR). Those disclosures began taking effect on March 10, 2021, for all EU financial market participants, and require asset managers to provide prescript and standardized disclosures on how ESG factors are integrated at both an entity and product level. This operates alongside Taxonomy Regulation, the EU Commission’s principal mechanism to address greenwashing, setting out criteria for determining if an activity is environmentally sustainable, including whether the activity contributes to (or does not significantly harm) one or more specified environmental objectives. With €7.6 trillion predicted to be invested in ESG by 2025, these regulations aim to help to reorient capital flows towards a more sustainable economy, foster long-termism and manage the increasing importance of sustainability risks.

Main Highlights

- In order for the 2030 EU climate target to be met, €350 billion annual increase in investments in sustainable businesses is required. However, defining what makes an investment or fund sustainable is a difficult task without clear guidelines or standardized reporting, and greenwashing is of particular concern.

- To increase transparency in the sector and to reorient capital flows towards sustainable and inclusive growth, two key pieces of legislation targeted towards financial market participants (FMP) are being rolled out: The Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulations (SFDR) and a new EU Taxonomy.

- The SFDR requires all financial market participants in the EU to disclose on ESG issues, with additional requirements for products that promote ESG characteristics or that have sustainable investment objectives. This affects all asset managers that raise money in Europe, regardless of where they are based.

- The EU Taxonomy is a classification system that is establishing a list of environmentally sustainable economic activities and will ultimately act as an investment rulebook.

- Though the regulations are directly aimed at FSAs, these new requirements will mean that any company with external investors will need to align with the SFDR and to anticipate the sustainability disclosure requirements of their capital providers. Companies who previously did not track or report ESGs will need to integrate sustainability more closely into their strategy, with large investors pushing them along this positive path.

- The current proposals for the EU Taxonomy have, however, been criticized by scientists and NGOs for allowing a green labelling of certain activities that significant harm to the climate and the environment.

Case Overview

In September 2020, the European Commission released its 2030 climate target plan, with an increased emissions reduction target of 55% by 2030 as compared to 1990. However, meeting this ambitious target will require a €350 billion annual increase in investments during the next decade (2021-30) compared to last. Sustainable finance is the process of taking environmental, social and governance (ESG) considerations into account when making investment decisions in the financial sector, leading to more long-term investments in sustainable economic activities and projects. This has a key role to play in delivering on the policy objectives under the European Green Deal, the Paris Agreement (which includes the commitment to align financial flows with a pathway towards low-carbon and climate-resilient development) as well as the EU’s international commitments on climate and sustainability objectives. It does this by channeling private investment into the transition to a climate-neutral, climate-resilient, resource-efficient and fair economy, as a complement to public money. Sustainable finance also encompasses transparency when it comes to risks related to ESG factors that may have an impact on the financial system, and the mitigation of such risks through the appropriate governance of financial and corporate actors.

Although it is reported that almost 90% of investors would like to invest in sustainable products, the sustainable finance landscape is difficult to navigate. Average investors want truly sustainable investment options, and new investments in sustainable funds more than doubled in 2020 compared to 2019, reaching a record-high of $51 billion, but just how sustainable certain funds really are is a matter of debate. A major critique of investments that take ESG into account is that there is really no such thing as a truly sustainable investment. With a prior lack of regulation around Sustainable Finance, it has been argued that the financial industry is often greenwashing investments, or making false claims about the sustainability of their products to profit off of the sustainability wave rather than taking meaningful action against climate change. With a lack of industry guidelines or standards, and inconsistent reporting, it can be very difficult for investors to distinguish between genuine and effective ESG risk-mitigation efforts and greenwashing.

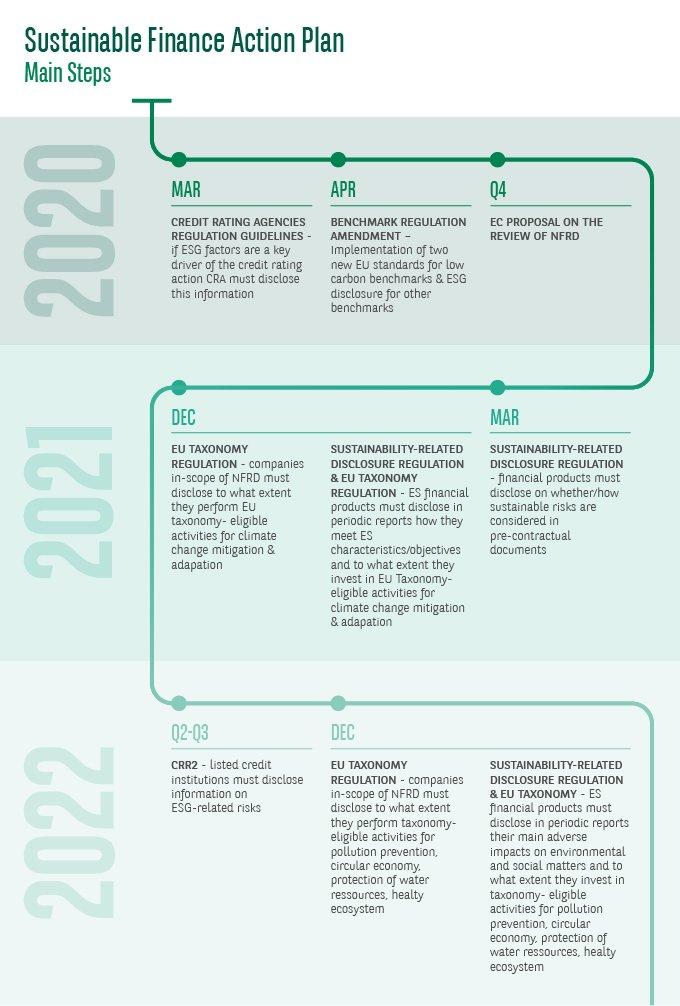

To mitigate these challenges, and encourage a shift towards increased sustainable finance, the EU has begun to roll out a Sustainable Finance Framework which is backed by a broad set of new and enhanced regulations that will apply across the bloc. This Sustainable Finance Action Plan (SFAP) has three main objectives: to reorient capital flows towards sustainable investment and away from sectors contributing to global warming such as fossil fuels; to manage financial risks stemming from climate change, resource depletion, and environmental degradation; and to foster greater transparency and long-termism in financial and economic activity in order to achieve sustainable and inclusive growth. Its two cornerstone regulations – Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulations (SFDR) and a new EU Taxonomy have begun to roll out in stages and together aim to create a level playing field across the whole EU, and are targeted towards financial market participants (FMP) such as asset managers, pension providers, insurance-based investors, and qualifying venture capital and social entrepreneurship activities. These complement the existing Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) which lays down the rules on disclosure of non-financial and diversity information by certain large companies.

SFDR, the first provisions of which began to take effect in March 2021, requires all financial market participants in the EU to disclose on ESG issues, with additional requirements for products that promote ESG characteristics or that have sustainable investment objectives. This regulation aims to limit the risk of greenwashing by financial market participants while increasing transparency, making it easier for end investors to understand how ESG and sustainability factor into their investments. SFDR affects all asset managers that raise money in Europe, regardless of where they are based. This means the new regulations have implications even for those funds offered to investors outside the EU.

The other cornerstone regulation of the Action Plan, the EU Taxonomy, is a classification system, establishing a list of environmentally sustainable economic activities. It aims to provide appropriate definitions to companies, investors and policymakers on which economic activities can be considered environmentally sustainable. The SFDR is linked to the EU Taxonomy, in that it defines the product categories that need to disclose Taxonomy alignment in 2022. Together, these regulations aim to limit the risk of greenwashing by financial market participants while increasing transparency and mitigating market fragmentation, eventually helping to shift investments where they are most needed.

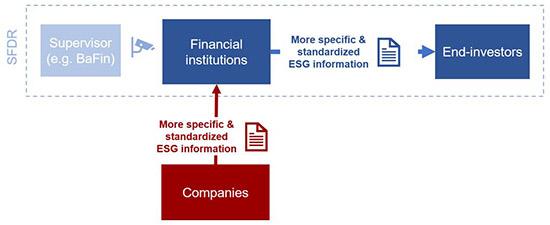

In practice, the SFDR requires that Member States’ supervisory authorities verify whether financial institutions are providing more specific and standardized ESG information to end-investors. In order to do so, these FMPs will need to obtain ESG information from companies in their capacities as investees, borrowers, and issuers. Businesses will therefore have to provide such information in a manner that aligns with the EU Taxonomy, to remain an interesting prospect for investors. This means that although the target of the SFDR may be financial institutions, it creates a trickle-down effect to corporations including those potentially outside of the scope of the NFRD – arguably the primary actors in transitioning to a climate neutral society.

Impact Statement

Sustainable investing supports a resilient economy and a sustainable recovery from the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. While the last few years have already seen a dramatic shift in market appetite towards sustainability-minded companies, the forecasts see further mobilization ahead; according to a study by PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), 77% of institutional investors will stop purchasing non-ESG products within the next 24 months and by 2025, €7.6 trillion will be invested in ESG. However, with no previous clear-cut criteria about what actually makes a company ESG investable, there is huge debate regarding what makes a sustainable investment. For example, the e-retailer Amazon, registered a carbon footprint of 51.17 million metric tons of carbon dioxide in 2019 — a 15% annual increase, yet some portfolio managers argue that Amazon’s commitment to reduce its carbon emissions and become carbon neutral by 2040 is a reason why the stock is ESG-friendly. Indeed, a Schroders survey acknowledged these challenges; difficulty managing and measuring risk – frequently due to a lack of good data and corporate and supplier transparency – was highlighted by most respondents, but the biggest challenge was found to be greenwashing, cited by 60% of respondents.

The new SFDR regulation is the first step in making these investments more transparent. It will

be significant in terms of additional disclosure and will unleash a flood of new sustainability information for investors to interpret. It will also likely catalyze strategic choices on how to approach sustainability as a firm. Through the implementation of this regulation, investors will be better informed to take decisions on sustainable finance issues by having access to increased quantity and quality of information when deciding on their investments and will allow comparison of products offered by different institutions according more homogeneous criteria.

However, the impact of the SFDR also relies heavily on the contents and scope of the finalized EU Taxonomy, which is the investment rulebook that will establish what the EU considers as sustainable investments. At the end of 2019, 123 scientists wrote to the European Commission about their concerns that the Taxonomy was not going to deliver climate neutrality by 2050, and in April 2021, WWF, alongside other NGOs, suspended its role in the European Commission’s Platform on Sustainable Finance following the release of the final climate taxonomy Delegated Act, in protest against both the greenwashing of the forestry and bioenergy criteria in the proposals, and the process that led to these criteria. The EU Commission has left a decision on the issue of whether to include fossil gas and nuclear energy – other areas that have come under harsh criticism – in the taxonomy for later in the year. Should the taxonomy allow for unsustainable industries to be classed as ‘green’, it will surely dilute its contribution towards the overarching goal of diverting much-needed investment into the sustainable industries that will create the most impact.

Systems Perspective

The Sustainable Finance Action Plan, while directly affecting FMPs, has a massive impact on other businesses as well. It is arguable that driving these developments is the critical role that private sector companies will play in addressing climate change, diversity, and other important societal issues, with large investors pushing them along this positive path. Companies, through the data they provide in sustainability reports and Non-Financial Information Statements (NFS), will have to report on the contribution of their business to sustainability. Investors will rely on this reported information to calculate the sustainable contribution of companies and advisors will assess which products fit with their sustainability policy. Companies that are aligned with the SFDR’s requirements can become more attractive to capital providers and have a first-mover advantage (such as better costs of capital) in comparison to other less sustainability-minded or resource-constrained companies. In this respect, everything is interconnected and the SFDR regulation cannot be isolated as simply affecting the financial sector.

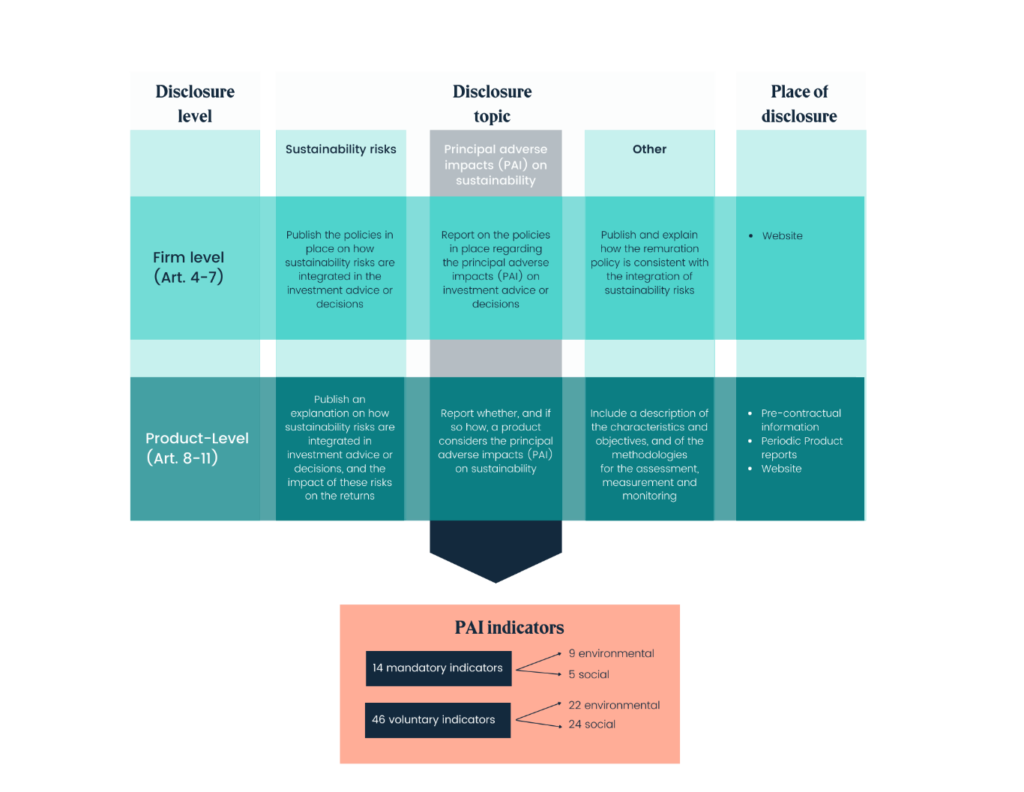

These new requirements will mean that any company with external investors will need to align with the SFDR and anticipate the sustainability disclosure requirements of their capital providers. This includes assessing the sustainability risks that may impact their own activities with quantitative and qualitative data, and producing internal reports, evaluating the principle adverse impacts (PAIs) of their own activities based on sustainability factors, including what actions were taken or are planned to remedy these impacts, and defining the strategic sustainability targets for their own economic activities. Businesses will need to consider the sustainability appetite of their existing and potential shareholders, investors and other capital providers, and will need to collect and maintain ESG information that is accurate, fair, clear, concise, and not misleading, and disclose it in their annual reports. Furthermore, they will need to apply methodologies to evaluate, measure, and monitor ESG matters, including identifying the main data sources and sustainability indicators. Overall, businesses that were previously not covered by the NFRD will now have to make more strategic choices on how to approach sustainability

Links and Contact Information

- Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulations (SFDR): https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32019R2088

- EU Taxonomy: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32020R0852

- Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD): https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32014L0095

Article by: Daniella-Louise Bourne and Puja Thiel, 4REVS researchers (and more)