Abstract

Seeds are the origin of life and 70% of the food we eat around the world. Different kinds of seeds can be grouped into three main categories. There are native seeds (which are original from the place they are sawn), creole seeds (which are from elsewhere but have naturally adapted to a specific territory), and genetically modified seeds, which are modified in laboratories around the world and chemically intervened aiming to increase productivity, reduce harvest times, and make them repellent of insects and plagues.

The issue with native and creole seeds is that most of the time they are not registered in the governmental entities that regulate food. Meanwhile, genetically modified seeds do have these certifications, given the fact that they majorly come from big enterprises. This situation has led to a series of regulations that different governments around Latin America (and the world) have applied to seeds, making illegal the use of non-registered seeds, thus, native and creole.

These regulations have a vastly negative effect on agricultural tradition, culture, and well-being of many citizens from the region, mostly those who live in rural areas and subsist thanks to agriculture. By limiting the number of seeds that a person can plant, use, or exchange, communities lose their agrobiodiversity, which plays an important role in culture and traditions. For example, a specific community can have a determined number of corn species and each one could have a different meaning or role (medicinal, ceremonial, nutritive, for youngsters, for elders). By prohibiting, controlling, or making illegal certain species, the immaterial cultural patrimony can be jeopardized. Additionally, the greater the variety, the greater the safety for the crops; if a plague was to affect one species, there would still be others that, due to their diverse characteristics, may not be affected.

By reducing the seed species that are legally allowed, the risk of losing entire crops is higher, as happened in Colombia in 2008–2009 with the cotton crops. Colombian cotton associations agreed with Monsanto (producer of genetically modified seeds) to plant their seeds, which were legally approved by the Colombian Government. When a plague reached the crops it wiped out the production and those who suffered were the farmers, since these seeds, although certified, did not have a guarantee. Situations like this have happened in different parts of the world like India, Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay.

For this reason, citizens from all Latin America have organized in groups called Seed Guardians, to guard original and agro-ecological varieties of seeds. This case portrays their story and struggle.

This Case Study is brought to you by Nelis’ 4REVS Research Program. Nelis is an NPO with an active and expanding network of young social innovators and leaders, sustainability practitioners, and creative minds from all continents (100+ countries) that enables us to provide experiential and on-the-ground knowledge. If you want to know more or be part of our network, please leave a comment! Or contact us in www.nelisglobal.org

Overall Description

Seeds are the origin of life. They are responsible for feeding the 7.8 million people that live on the planet right now and represent the origin of 70% of the food around the world. With each migration, seeds have traveled the world, spreading and adapting to different climates, terrains, and environments. Not every “traditional” species from a specific region or country originated there. For example, tomatoes are an Andean species. Only until the Spanish violent conquest of America were they taken to Europe, being today one of the main ingredients in Spanish and Italian cuisine.

Seeds are also culture and tradition, are the origin of food, medicine, housing, tools, material culture, rituals, and ceremonies. They have traveled the world, adapting each time to the different places they have arrived, bringing their benefits to different civilizations and cultures around the whole world.

Seeds and immaterial culture

In Latin America, peasants, afro, and indigenous communities usually have artisan and traditional techniques for the conservation, production, and selection of native and creole seeds. The adaptation techniques and processes applied by these communities are essential to avoid the harmful effects of global warming because thanks to the work of these communities, some of these plants can adapt to different climates. These artisan techniques are the main allies for these communities to achieve food sovereignty and food security since they make the seeds resistant to the specific conditions of their territory.

Seeds represent freedom because with them a person can have an important degree of stability and independence; by harvesting what the plants give one can meet some basic needs such as housing, health, and food. It also opens the possibility of having a vast agro-biodiversity.

How are governments involved in this situation?

However, companies and governments around the world have different plans for seeds. On the one hand, some companies produce Genetically Modified Organisms (GMO), which are organisms such as seeds that are genetically intervened. As a result, for 2014, 82% percent of the seeds in the world were patented, and 77% of those belonged to only ten companies. On the other hand, different governments around the world, like the Colombian, benefit these GMO seeds over the creole and native seeds, making it illegal to produce, sell, or plant the latter. And they do not only benefit the patented seeds but also deny the possibility of saving the creole and native seeds, to the extent that they even prosecute anyone that does it. With different laws, governments have criminalized the free circulation of seeds, and in turn, every tradition and culture related to seed conservancy and ancestral agriculture.

Luckily, in Colombia laws have been changing lately. Things have evolved from legal frameworks that prohibited seed saving and distributing (even if it was for free), to legal resolutions that protect the right of families to store seeds to protect creole and native seeds.

Resolutions like the 970 adopted by the ICA (Colombian Agricultural Institute) in 2010, which “controls production, storage, commercialization, and the free transfer and/or use of seeds, in the country”, was a law that prohibited peasants (and any Colombian resident), to store seeds from their crops, only allowing to buy them from “certified” seed producers. In simple words, this meant that anyone who ate an apple or peach couldn’t plant the seeds because it was illegal, and doing it could end up in financial fines and even jail time.

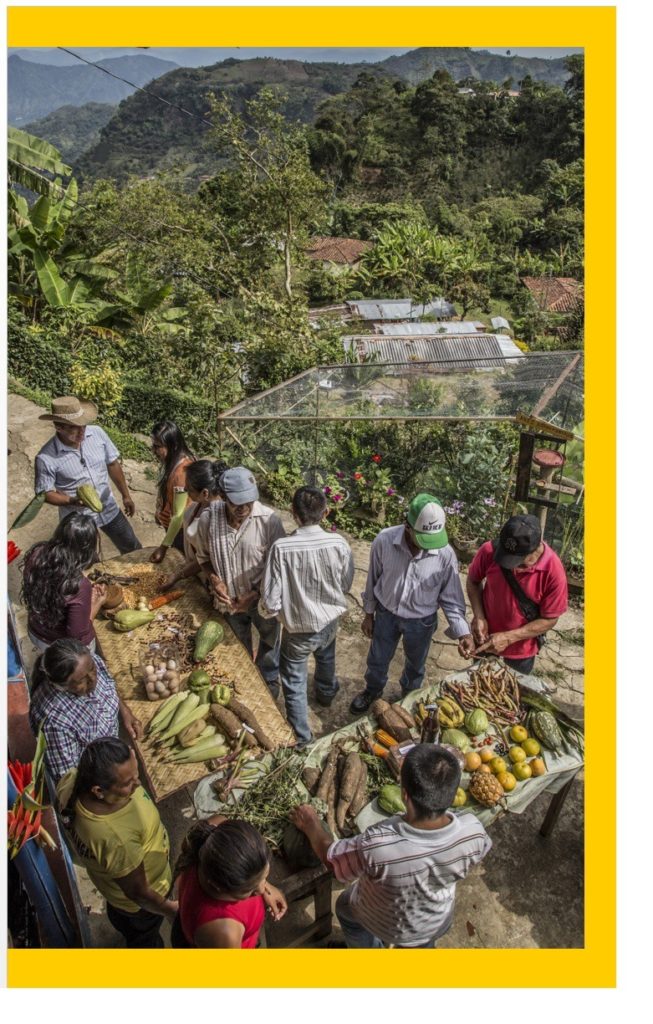

“Seed Guardians”, the seed revolutionaries

Laws and resolutions like these cannot only be found in Colombia. This is a situation that afflicts all of Latin America and even other countries around the world. Fortunately, the sense of belonging of people has been stronger. In response to this sea of resolutions and legislation, organized groups of citizens, mostly peasants, afro, and indigenous communities, are beginning to gain visibility and strength. These groups of people work for the conservation and sovereignty of creole and native seed variety to return these seeds to and keep them in the hands of those who care and fight for their preservation. They are called “Seed Guardians”, and they work every day to protect the agrobiodiversity in their territories.

Thanks to the hard work, pressure, and resistance exerted by Seed Guardians and allies, today in Colombia there is the resolution 464 from the Minister of Agriculture and Rural Development. This resolution protects traditional seed conservancy techniques and the right to collect, save, and plant seeds that are not “registered”, but those that peasants obtain from their crops or as an exchange with others who develop the same activity.

Finally, it is important to acknowledge that this situation is different in each country and that in Latin America there are still countries fighting for their seed sovereignty, which in the end is a fight for their food sovereignty. Also, in Colombia, although its process can be perceived as an example of the victories obtained by the Seed Guardians in terms of seed legislation, there is still a long way to go to ensure food sovereignty and food security.

What do food sovereignty and food security mean?

According to the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) number 2 -Zero Hunger- of the United Nations (UN), governments, companies, and individuals should direct their actions to reach a zero hunger world by 2030. Under this goal, there are two important concepts that, if accomplished, will put countries one step closer to combat and eventually eradicate hunger. These concepts are food sovereignty and food security.

Food security: ”Food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences to lead a healthy and active life.” (FAO, 2006)

Food Sovereignty: “Is the right of people, communities, and countries to define their food policies that are ecologically, socially, economically, and culturally appropriate to their circumstances, claiming food as a right.” (International Peasant’s Movement).

The main difference between both terms is the autonomy given to the community by the notion of food sovereignty, as this establishes that they can define their policies. For this reason, Seed Guardians fight for it, because they need the autonomy to work the land the way their traditions have taught them.

Where are Seed Guardians Located?

These are some examples of Seed Guardians organizations around Latin America: Ecuador, Perú, Chile, Argentina, Colombia, Uruguay, Brasil, Mexico, Venezuela. However, it is important to keep in mind that this is an activity that happens mostly in the countryside of the so-called developing countries, therefore many of these organizations may not have websites to be found.

Main features or highliths

- ●Regional movement: Latin America is a region of the world where the traditional connection to the land, its agriculture, and rurality still prevails in certain sectors of society. As a consequence of this connection to rurality, peasants’ associations are usually strong. Indeed, they do not only exist in their specific territories but tend to connect, working as a unified region to solve together the problems that affect them.

- ●Women: Seed guardians are usually women because of the relationship that both of them have with life and how they both represent the origin of it. This does not mean that men cannot be seed guardians. However, this is the tradition that is usually followed.

- ● Different ways of preserving the seeds: Each group of guardians has different ways of preserving the seeds depending on the climate, humidity, and especially the local culture. Many keep them in refrigerators, others underground in glass jars, others in cupboards, and finally, there are others such as the seed guardians of Putumayo, Colombia, who keep them “underground.”

For this community, preserving the seeds “underground” means that the seeds are not well-preserved if not sown. They say that if the authorities come to control them for the reproduction of native seeds, there is no better place to keep them than within the same crop. This decision is related to their specific cosmogony and culture, in which seeds do not develop their full potential unless they are integrated within the cycle of life.

- ● Creole and native seeds: The difference among these two seeds is that the native seeds are original from the specific territory, while the creole seeds have their origin elsewhere and have been naturally adapted with time to the context.

- ● Law has been changing: Thanks to the activism and strength of seed guardians and other groups that support them, countries like Colombia currently have laws that protect the right to save and select native and creole seeds. This is a big change compared to the laws issued in this same country in the last decade.

- ● Vandana Shiva: Vandana Shiva is an Indian activist who fights for food sovereignty and for the rights of those who work the land. She has been a strong ally in the process of reclaiming seed sovereignty in Latin America and all around the world, and she has closely accompanied the groups of seed keepers and their cause.

- ● Seed “economic systems”: There is a whole economic system within the seeds guardians groups. Seeds are not necessarily sold, and although some do sell them, it is not the most common practice.

There are two ways of transferring seeds from one person or group to another.

○ One is to exchange seeds with each other to have a wider variety of species.

○ The second one is the seed loan, which is by far the most interesting modality since it implies great responsibility from the person asking for the loan. In this case, the owner of the seed lends a seed until the second person gets his first harvest and manages to recover those seeds again, at which point he returns them.

● 3 types of involvement with the movement:

- ○ Seed Guardian: Seed producers, who preserve, recover, select, and research about seeds to bring the best of each species while preserving agrobiodiversity.

- ○ “Semillista” (in Spanish) or Seed grower: They are the future Seed guardians which are in a learning process and a transition from conventional agriculture to agroecology.

- ○ Friends with the seed: People who support the movement economically or by working in different activities needed to achieve the Guardians’ goals.

Why is this Revolutionary?

A figure of food sovereignty and security: Several factors make the Seed Guardians movement crucial to achieving food security and sovereignty.

- ○ First, the fact of having the autonomy to conserve, reproduce, and share seeds represent the possibility of every human being on the planet to grow their food through the seeds that they are provided with.

- ○ Second, by seeking the protection of native and creole seeds, agro-biodiversity is being protected. Diversity is the key to the protection of all species since in the case of a catastrophe or plague within a context characterized by the homogenization of seeds, all of them would be condemned to suffer it. Diversity means that if some seeds suffer damage, the others might survive given the difference in their particular characteristics.

● A much needed revolutionary act: As a consequence of governments regulating seeds through different seed policies, sowing native and creole seeds is a revolutionary act. Also, protecting, exchanging, and in general, managing these seeds is also a revolutionary act, and more when these groups of people not only do what they do but also teach others to do it as well.

● Positively affecting the government’s decisions: The Seed Guardians’ social movement and its allies have managed to put pressure on government entities and influence policy changes. Much progress is still lacking in peasant and seed rights legal frameworks. However, the Seed Guardians have already demonstrated the impact that they can achieve.

Concrete examples

Example 1

Interview with Isabel Guevara, Seed Guardian in Bogotá, Colombia

Since Isabel Guevara was a little girl, her father taught her and her siblings that seeds should be preserved. Not every product in harvest was for sale; it was important to take some of the production to the animals, another part was meant for their consumption, some products were for selling and some were saved to extract the seeds and save them.

She lived in the countryside, until one day, 45 years ago, she arrived in Bogotá, the capital city of Colombia.

What she missed the most from this transition was the action of growing her food, because where she came from she did it daily. Isabel began planting again, this time in pots, until one day one close friend told her about a program that the Botanical Garden of Bogotá was doing: an urban agriculture workshop. These workshops were born from a collaboration among organizations, including the Japanese International Cooperation Agency (JICA) and the Bogotá Botanical Garden.

Thanks to this workshop she understood that agricultural activities could also be done in the city and that she could continue her seed reservoir, even where she was now. From this moment on, 17 years ago, Isabel was officially the Seed Guardian of her community and a member of the Free Seeds Colombian Network. She has worked in the urban orchard of her neighborhood ever since.

What is the Free Seeds Colombian Network?

Isabel: “This is the main seed network in Colombia. It works with people, mainly in the rural areas, that want to contribute to the seed conservancy in their territories. It is an ally of the Guardians of the Life Network, an organization with the same mission but in Ecuador.”

Why is it important to protect our seeds?

Isabel: “Seed conservation is important since the moment we began moving around the earth. From the moment we are born we are a part of the ecosystem, just like seeds. As the world is shaping and ‘developing’, there are policies where it is now defined which seeds are useful and which ones are not, few varieties are chosen, and what about the rest of the seeds? They remain in oblivion, buried, they do not come out again and that has been the greatest concern for us because our children will not know the true nature and variety that exists on earth.

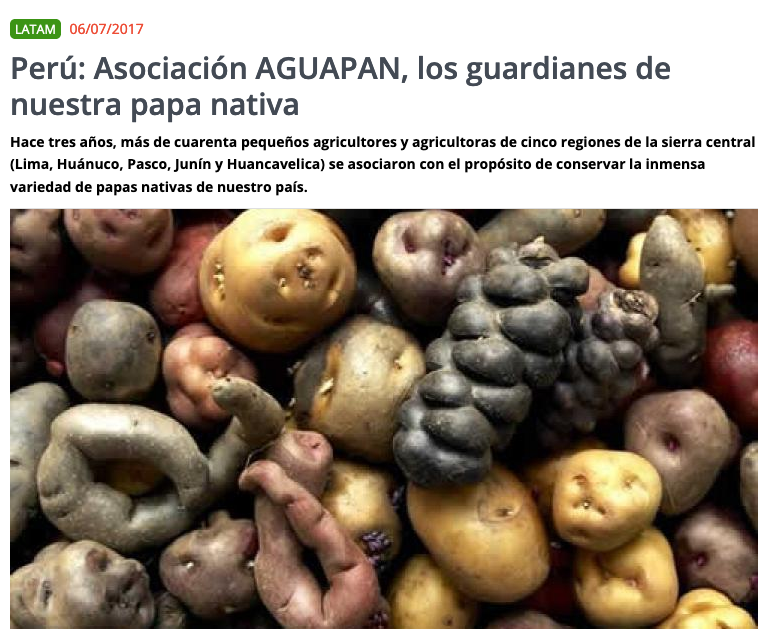

The seed variety that they [the government] allow us to eat is not nourishing us anymore, they only let us eat chemically modified seeds that gives better productivity, but they forgot about the others. We are working to make our future generations remember and get to know the different potato, corn, and bean varieties, for example, to explain to them that there are more kinds of these species than the ones one can find in a supermarket.”

Example 2

Quito, Ecuador

One of the main goals reached by the Seed Guardians in Quito was to rescue more than 1.500 species of the vegetable variety. They also built 18 educational seed centers, led by seed guardians, in which they preserve seeds but also teach other people about these practices.

Article by: Sara Gómez Gómez, 4REVS researcher (and more)